Please note - this post is written using identity-first language (e.g. ‘an autistic person’) due to research and lived-experience suggesting preference for this within the neurodivergent community as a way of recognising inherent experiences. We recognise that identity language is individualised, and preferences may vary. When possible, please respectfully ask neurodivergent individuals their personal preference.

What is Neurodiversity?

Neurodiversity is a term coined in the late 1990’s by autistic sociologist Judy Singer, that describes the rich diversity of human minds resulting from normal variations in the human genome

Neurodiversity includes both Neurotypical (NT) and Neurodivergent (ND) brains

In most cases, our neurotype is developed in utero, meaning it generally is not something that will change as we grow and develop. If someone is born Neurodivergent, they will always be Neurodivergent (however, due to the nature of ND-traits, such as social-communication differences when compared to NT-traits, these may not be noticeable for many years leading to delayed neurotype discovery). Exceptions to this can be resulting from injury or trauma, where someone’s neurology may diverge

What does it mean to be Neurodivergent?

Neurodivergence is a term that describes any neurotype that is atypical, or different to the standardised norm (AKA not Neurotypical)

Examples of Neurodivergence include autism, ADHD, and dyslexia

Neurodivergent minds experience the world differently to Neurotypical minds. This can show up in difference in thinking styles, movements, interactions, and sensory processing

Research is growing in the space of Neurodivergence and eating disorders, however currently, most of the research has focused on the intersection of autism and Anorexia Nervosa which is what will be explored further below. Despite this, it is important to note that Neurodivergent people can experience any type of eating disorder.

The intersection of Autism and ED’s

“Same behaviours, different reasons”.

Research suggests that up to 1 in 5 autistic adults will experience an eating disorder in their lifetime [1]

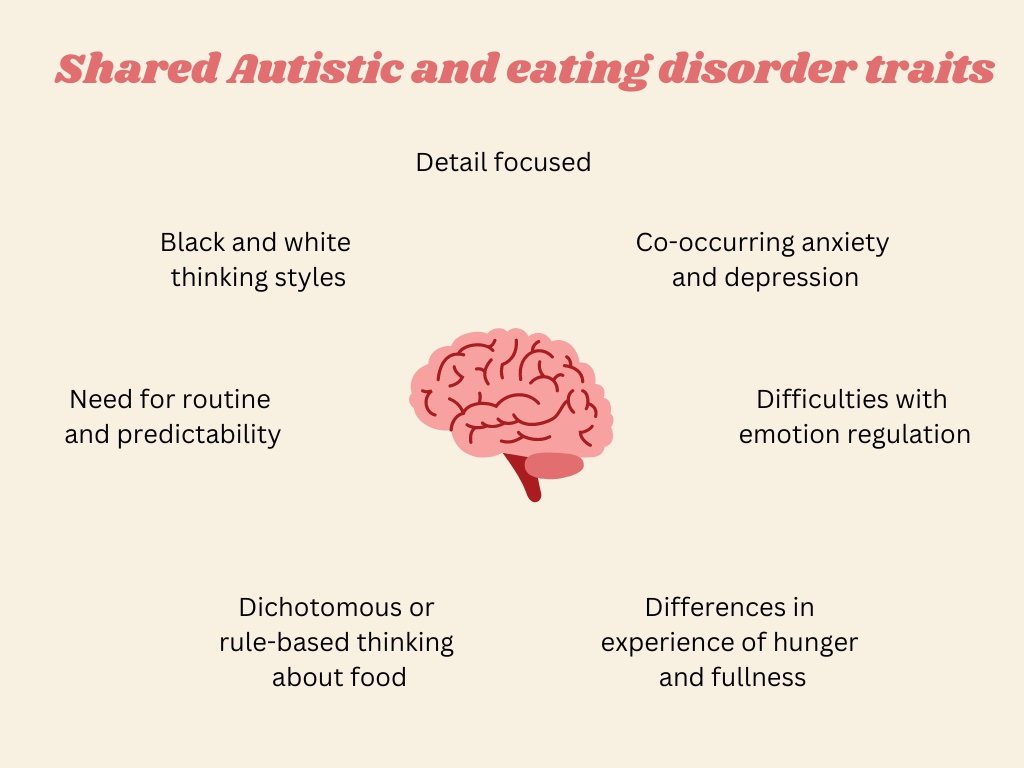

There are several traits associated with autistic minds that can be seen in those with Anorexia Nervosa that may explain this high rate of co-occurrence (see table below)

What does this mean for support?

Autistic people with Anorexia Nervosa can expect longer inpatient stays and poorer outcomes with traditional treatment approaches when treatment approaches are not adapted, comprehensive, and individualised [1]

Providers need to keep potential existence of sensory processing differences, intense passions, hobbies, and interests, need for routine and rituals, and interoception at the forefront for assessment, diagnosis, and treatment

Support needs to be inclusive, enabling, and affirming to honour and reflect the unique needs of the individual

A note on autism for those assigned female at birth (AFAB):

There are far fewer AFAB people identified as autistic when compared to AMAB (assigned male at birth) people, however, this may not be an accurate reflection of the gender ratio in autistics. Possible explanations of this include autistic AFAB individuals showing less overt autistic behaviour due to gender norms when compared to AMAB people, and a bias towards AMAB people in the diagnostic criteria and assessment tools [1]

This leads to AFAB people being diagnosed much later in life – or not at all

Research has shown that this missed or delayed diagnosis can lead to an increased likelihood of developing secondary mental health concerns including Anorexia Nervosa [2]. This can further challenge an autistic neurotype discovery if the eating disorder manifests in extreme rigidity and/or obsessive interest in calories or exercise [3].

References

[1] Westwood H, Tchanturia K. Autism Spectrum Disorder in Anorexia Nervosa: An Updated Literature Review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017 Jul;19(7):41. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0791-9. PMID: 28540593; PMCID: PMC5443871.

[2] Yaull-Smith D. Girls on the spectrum. Communication National Autistic Society. 2008.

[3] Lai M-C, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013–27.